This is for all of us and the histories we’ve lived

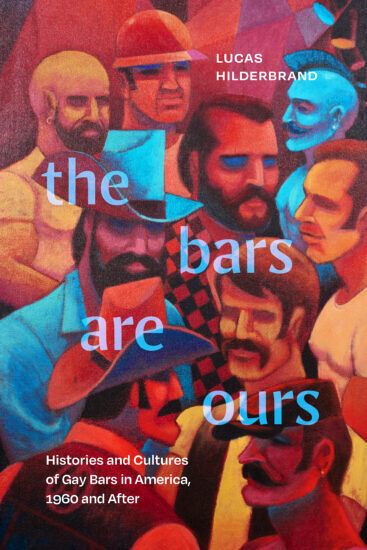

Lucas Hilderbrand

The bars are ours

For many queer people, the gay bar is a rite of passage. We discover our family of choice and, perhaps, meet a hook-up or spouse. We toss dollar bills and get sloppy, knowing that our besties have our back. Throughout history, these spaces have helped define our culture by pushing boundaries and providing safe spaces for subcultures within the LGBTQ+ community.

Lucas Hilderbrand’s The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America, 1960 and After offers a panoramic history of gay bars, showing how they served as the medium for queer communities, politics, and cultures. Hilderbrand canvassed the country to unearth the evolution of these spaces, from Chicago’s leather scene and Kansas City drag to San Francisco’s iconic venues and the emergence of Latinx venues in Los Angeles.

While the definition of queer spaces continues to evolve, Hilderbrand writes, “The potential for same-sex sex is what makes gay bars gay. Yet whereas historically common cruising venues such as bus stations, parks, and department-store restrooms all afford anonymous sex, bars offer social contact as well. Bars rely on a mix of familiar faces and new connections. Indeed, the presence of strangers is as important as the company of friends.”

GayCities offers an exclusive excerpt from the author’s expansive 464-page text (which also includes 98 illustrations that offer a visual roadmap of queer nightlife) that profiles Chico, a Latinx gay bar in Montebello, California, 8 miles east of downtown Los Angeles.

Chico, Montebello, California

Chico (boy) came out of a different context: providing a homegrown space on the east side to serve Chicano men attracted to masculine men at the turn of the millennium. The Chico scene refused the homonormative version of gay and lesbian life gaining mainstream acceptance at the time and offered an alternative that read as more authentic to its patrons–though one that was just as open to fantasy. Here the “boy” connotations differ significantly from those in San Francisco a decade and a half earlier.

Chico eroticized and reproduced a performative image of Latino masculinity–the cholo, homothug, homiesexual–as an alternative to the whiteness of West Hollywood, the twinks at Circus/Arena, and the vaqueros of Tempo. The club also exuded a defiant edge that was missing from pop acts such as Ricky Martin, Enrique Iglesias, Marc Anthony, Christina Aguilera, Shakira, and Jennifer Lopez, who were collectively ballyhooed as constituting a crossover Latin pop explosion at the time.

Significantly, Chico opened after a circuit of east-side Latina women’s bars, such as Redz, the Plush Pony, and the Sugar Shack, had operated for decades; these bars overlapped for a time. Men were often tolerated in these prior spaces as long as they respected the women; queer communities also coalesced in otherwise straight venues. Despite its avowed masculinity (and perhaps the unacknowledged influence of butch lesbian styling), Chico’s culture as a neighborhood venue perhaps more closely resembled these Chicana women’s bars than the venues in Hollywood.

Chico opened in 1999 after bartender Julio Licon introduced Marty Sokol, a Jewish TV producer from the East Coast, to an existing dive bar in Montebello and suggested remaking it as a new kind of gay bar. They bought it and did so.

Chico’s debut ad featured a male cartoon character with a mohawk, white T-shirt, wide-legged pants, and a mischievous grin. The text above the figure states, “Lo que todos esperabamos” (What we’ve all been waiting for), and the tagline proffers, “The new spot for mi gente” (my people) in Spanglish. The bottom text states, “Nuevo dueño. Nuevo Aventura. Nuevo lugar.” (New owner. New Adventure. New place.) Information about open days and location appears in English. The ad, featuring text in both Spanish and English but nowhere translating, specifically targeted a fluidly bilingual audience able to code-switch between languages; this contrasts with the dual address of publicity materials for venues that do translate. Soon, the bar’s imagery transitioned to photos by Dino Dinco featuring men with shaved heads, often shirtless and in cars evocative of low riders.

From the start, Chico cultivated what Richard T. Rodríguez has aptly termed a queer homeboy aesthetic. The venue at once recognized a specific southern California Latino cultural formation and situated it away from the existing gay venues.

A fascinated Los Angeles Times reporter explained the scene to those uninitiated: “The clientele [is] a mix of homeboys, ex-gangbangers, cops and guys who trek out from West Hollywood, the desert and the San Fernando Valley in search of something edgier, more urban. ‘Tough, masculine-looking guys. Rough, bald guys. That’s Chico,’ says [bartender] Licon. ‘Straight people come in and they still don’t know it is a gay bar.’ And, even when they do, some stay for the party.”

Signaling that the bar’s image is largely that–an image–or possibly to quell reader anxiety, the reporter then discloses that a tattooed go-go dancer “has never been in a gang.” Chico’s parties were so successful in creating a new scene that in the early 2000s, Tempo hosted a rival party called Club Ghetto to capitalize on the cholo homeboy aesthetic.

Offering a concurring, insider’s viewpoint, Joël Barraquiel Tan recalled that “sure enough, there were Homothugs everywhere. Black and brown, varying ages, pressed khakis and drooping jeans, drinking Alizé and Cuba Libres, smoking Newports, and affecting ghetto fabulous.” [Dino] Dinco, who helped construct the bar’s image, told us that early on, 90 percent of the bar’s crowd had shaved heads and baggy pants–reflecting the cholo aesthetic, which had a strong erotic charge. But the look eventually shifted, both because personal style changed but also, he suspects, when “posers” likely got sick of harassment from the police. Chico endured hostility from both bigots and police in its early years, though both subsequently diminished as LGBTQ+ life became more normalized in the culture at large. Later marketing invoked the term chulo (pimp and/or handsome) rather than cholo.

Chico continued to evolve–for instance, by hosting the monthly queer Latinx punk party Club sCUM, dating from 2016. This party was promoted by Rudy Bleu and Hex-ray Sanchez (as Noche de Jotiar–Night of Faggotry) rather than by the bar; they wanted to make their queer Latinx party more geographically accessible to its constituents than existing parties.

This strategy of manifesting alternative queer formations via recurring parties dates back at least three decades. Bleu and Sanchez initially pitched the night as featuring Morrissey and British new-wave music Because the sound seemed more bankable; when they packed the house, they felt emboldened to make the set lists more punk. The popular event also traveled to San Francisco (at El Rio and the Stud), New York City, and Mexico City, connecting with a queer Latinx punk diaspora.

In 2006 Chico’s owners also bought the gay bar Rawhide in the San Fernando Valley and renamed it Club Cobra, where they reproduced the Chico scene and often shared the same staff and performers. During the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns, Club Cobra launched an OnlyFans page to promote its dancers. Chico closed its physical venue in 2020 and briefly resurfaced as a recurring party in West Hollywood while Club Cobra resumed operations in its own space. Chico reopened in its original location in summer 2022.

Scenes from Chico, 2019

Chico in Montebello is in a small strip mall across a busy thoroughfare from a Super A grocery store. The bar is relatively small: a one-room venue with flocked red velvet wallpaper and a large tavern-style bar to the left of the entrance. It’s a neighborhood bar cum nightclub. We carpooled to Chico with friends Josh and Albert for Cockfight, a weekly boxing-themed night that culminates in a title match between two go-go boys in boxing shorts. The social media posts for the night play up the long-standing connotation of hypersexualized Latin lovers. The crowd was small, chill, and more gender-and age-mixed than we expected; the marketing had been suggestive of a raunchy party.

The music was a mix of Latin pop and reggaetón, but the mounted TV screens showed videos for Anglo pop that didn’t match what the DJ was playing. Whereas the music was in Spanish, the marketing and the competition commentary addressed the audience in English. The Cockfight competitors were introduced as hailing from Honduras and Tijuana, respectively. Alex, the beefy dancer from Honduras, seemed like he was probably straight; he danced looking at himself in the mirror rather than at the crowd. Kike, the more lithe dancer from Tijuana, was more ambiguous in his sexuality; he was friendlier with the crowd, although he repeatedly stopped dancing to look at his phone while on the podium.

When the competition was underway, one patron made it rain by tossing single after single onto Kike as he danced. Kike won the match based on crowd cheers; it was unclear if nationalist pride played a role in the crowd’s favor or if it was primarily his endowment. After the show, as the manager was disassembling the miniature boxing ring, Josh asked if one of the dancers was a returning champion defending his title. The manager matter-of-factly explained that both dancers were new because the previous week’s winner had been deported.

By Lucas Hilderbrand with Dan Bustillo. Excerpted from The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America,1960 and After by Lucas Hilderbrand. Copyright Duke University Press, 2023.