I first visited Florence as a deeply closeted college junior. Naturally, my first order of business was to see Michelangelo’s David. For once, I could openly examine each sublime detail of a naked man, from brow to big toe. And I wouldn’t have to pretend otherwise. Even the straightest of straight men paid homage to Michelangelo’s twunk.

And yet I didn’t go see David on my first day. Nor the second. Nor the third. Was I afraid l’d lose control of my deeply repressed desires and run amok right there in the gallery? Was I avoiding the inevitable truth that my ideal man was, in the end, just a hunk of marble? Was I unconsciously edging?

Probably all of these applied. Ultimately another much happier reason kept me away. I was too busy discovering all the other naked Florentine dudes. They filled its museums, its public squares, even its church walls!

These days, I don’t have to cross the ocean just to experience a little male nudity. When I returned to Florence this winter, I could gaze on the naked statues of David and Neptune and Adam with a more serene mind. As I did, it occurred to me that, while gorgeous in themselves, they also tell an intriguing history of Florence itself.

Roman free-for-all

We don’t usually associate Florence with the Roman past. The city doesn’t have a single ancient ruin of any significance—no aqueduct, no amphitheater, no crumbling colosseum. Yet Florence was actually founded by Romans. Around 59 BC, soldiers from Julius Caesar’s army constructed a military garrison and the banks of the Arno River, which grew into the city we know today.

Obviously, male nudity was not just acceptable to the Romans but practically de rigueur. Butt-naked gods adorned their temples and unclothed gentlemen gathered daily in public baths. Florence’s ancient baths and temples have all but disappeared, but the imprint of Rome is still visible, if you know where to look. For example, the grid of streets between Piazza Signoria and the Duomo follows the layout of a classic Roman military garrison. And the Gallerie degli Uffizi and the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze preserve plenty of evidence of this body-positive phase in Florentine history.

In the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, you can see these two beauties on a ceramic plate. Before Rome conquered the region, Etruscans ruled the area from hilltop Fiesole, just north of Florence. The Etruscans were enamored of Greek culture, and the Greeks were enamored of naked men. So, we get this delicate and intimate vase painting from around 400 B.C., in which a younger man helps his bearded daddy put on a leather bracelet. Believed to be an Etruscan copy of a Greek original, it was discovered a few miles south of Florence.

Like the Etruscans, Romans were also hardcore devotees of Greek culture. And this bronze fellow, who also lives in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, is believed to be a Roman copy of a Greek original. Originally cast around 30 BC, he was rediscovered during the Renaissance and eventually became a wedding gift for Ferdinand II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and his wife Vittoria in 1633. Today, he is known as “Idolino.”

The bride should have been suspicious when her in-laws honored her marriage with this statue of a beautiful young man. As we shall see, male nudity had fallen out of fashion by the 1630s. It must have suddenly made sense when, just a few years later, Vittoria found Ferdinand in bed with his male page.

Bathed in sensuous natural light, this Roman copy of Polykleitos’ Doryphoros stands guard at the end of a vast corridor of the Gallerie degli Uffizi. Little is known about his origins or how the Medici acquired him. However, modern scientific techniques have demonstrated beyond doubt that this Doryphoros is bootylicious. I include him here because, in the words of the noted aesthetic philosopher Sir Mix-a-Lot, “I like big butts and I cannot lie.”

Medieval censorship, Renaissance revenge

As the Roman Empire fell into decline after 400 BC, the Catholic Church became the most powerful institution in Europe. Unfortunately, the Church tended to hate sexuality, and the human body generally. And since it was the only institution in medieval Europe with the cash to spend on art and beauty, images of naked men plummeted almost to zero after 400 AD. Only Adam and Eve in the garden, or souls being tortured in Hell, were depicted without clothing—and only then if their primary sexual characteristics were hidden from view.

By 1400, the Church’s stranglehold on culture began to break down. Thanks to its excellence in both cloth-making and international banking, Florence had enough cash to support their own cadre of artists. At the same time, Florentines began to see themselves as the inheritors of the Roman Republican tradition. They looked to classical art to inspire their own. And gradually, Florence embraced many cultural values too, including the idea that physical beauty was not a sin, but actually could serve a higher moral purpose.

Florence’s embrace of nudity begins with Massaccio’s “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.” Painted on the walls of the Brancacci Chapel around 1425, it depicts Adam as a jock who seems to have left his fig leaf back in Eden. A generation, Adam’s junk would surely have been hidden in shameful shadow. Here, Massaccio makes the light shine brightly on those most intimate bits of his anatomy.

In doing so, Massaccio actually contradicts the Bible itself. According to Genesis, God made sure Adam and Eve were clothed in animal skins before he kicked them out of Paradise. Happily, Massaccio decided to go rogue. Lovely to behold in himself, Massacio’s Adam encouraged lots more male nudity in the coming century—and was a major influence on the work of no less than Michelangelo.

In the 1440s, Donatello, considered the greatest sculptor of his generation, followed Massaccio’s lead and portrayed David, the slayer of Goliath, in nothing but his boots. His David, probably commissioned by the ruling Medici family to adorn their private palace, is the first freestanding nude male sculpture made since the fall of Rome.

Most remarkably, David’s nudity is not a symbol of shame or defeat. Rather, he stands in triumph, his foot atop the decapitated head of the tyrant Goliath. Clearly, Florence was learning to like, even celebrate, the idea of a naked man in their midst. Today you can visit him, along with many more naked men, at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello.

Some 50 years after Donatello cast his bronze David, Michelangelo decided to up the ante. His marble David doesn’t even bother with footwear. Most remarkably, Michelangelo’s David wasn’t commissioned for a private home, like Donatello’s. On the contrary, he stood proudly in the Piazza della Signoria, the city’s main square, for almost four hundred years.

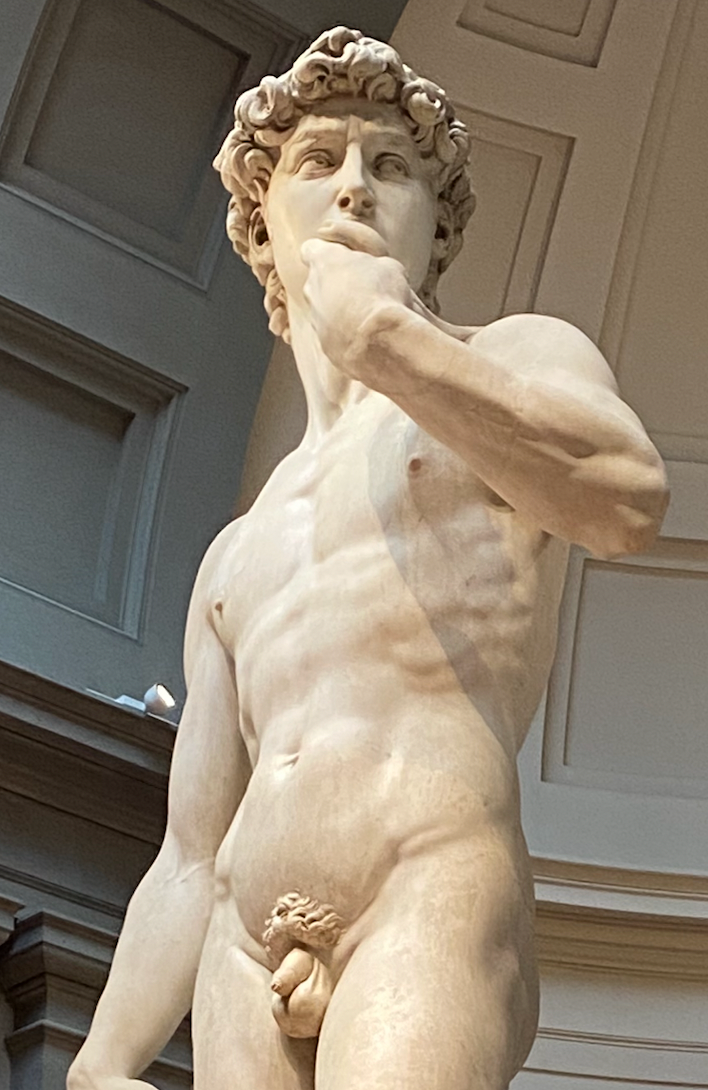

To protect him from the elements, Michelangelo’s David now lives in the Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze, where I first laid eyes on him back when I was a closeted twenty-year-old. The crowd included a fair share of frat bros who would surely have bullied me if we had gone to the same middle school. Yet, even the bros were in awe. Those huge hands. That mane of hair. That impressive v-line points all eyes toward his willy.

To behold David is to pay homage to male beauty.

The bros and I moved closer and found that Goliath’s killer isn’t just ripped. He ripples with life. The tendons of his strained neck threaten to snap. His skin stretches tight across the sinewed torso, yet grows soft and velvety around his shockingly lifelike privates. Straight or gay, you can’t help but want to touch David, if only to understand how stone can become such exquisite flesh and bone.

This bearded gym daddy, a.k.a. Bartolomeo Ammannati’s Neptune, stands smack in the middle of the Piazza Signoria. Commissioned by Duke Cosimo I de’Medici in 1559, Neptune—the Roman god of wind, storm, and sea—outmuscles Michelangelo’s younger, leaner David. Regrettably, his diet and exercise regime is lost to history. Nor do we know whether he sought help from steroids. However, he is a little stiff and wooden, not unlike a few muscle queens I’ve known.

Ammannati’s burly Neptune represents the apex of the Florentine love of full-frontal nudity. Michelangelo still had to justify David’s marble member by connecting it to a biblical story. Ammannati, by contrast, abandons all Christian pretensions. Those thunder thighs belong to an unapologetically pagan god—one who, more than once, is said to have slept with mortal men.

Stripping away 300 years of fig leaves

Unfortunately, in the 14 years between the commissioning of Neptune and his completion, attitudes toward nudity were changing quickly. Shortly after completing his massive Neptune, Ammannati disowned his own work, saying nudity was a sin and a disgrace and should never have been depicted in art.

Why did the thought police raid the penis party? In a nutshell, Protestant Reformers like Martin Luther accused the Catholic Church of financial and moral corruption. And by the 1560s, they were gaining serious traction. In response, a repentant pope decided it was time to cover all the exposed phalluses with fig leaves and loincloths. Not even Michelangelo’s David was spared.

Is it a coincidence that the so-called Fig Leaf Campaign coincided with Florence’s (and Italy’s) long, slow decline? I’ll let the reader decide.

As the cultural power of religion waned in the 19th and 20th centuries, sexuality and the body staged a dramatic comeback. David was relieved of his fig leaf in the early 20th century. Gradually over the following decades, the city’s willies have been liberated from their fig leaves. Among the last to be freed was Massaccio’s Adam. His man parts, covered by foliage in the 1600s, were first exposed by a major restoration in the 1980s.

I am grateful to have come of age after Florence had stripped away all the offending fig leaves. And I don’t think it is a coincidence that, just a few weeks after visiting the city, I boldly admitted to a friend that I might possibly not be 100% heterosexual.

Related:

Don't forget to share: